Giant trees still fall amid old-growth funding lag for BC First Nations

November 27, 2022

The Canadian Press

By Brenna Owen

British Columbia has asked First Nations if they want old-growth forests set aside from logging, allowing time for long-term planning of conservation and sustainable development, but it has yet to fund the process on a large scale, advocates say.

In the meantime, some of the biggest and oldest trees are being cut down.

Several years before the BC government launched the process last November to defer logging in old-growth forests at risk of permanent biodiversity loss, Ahousaht First Nation was developing the land-use vision for its territory on Vancouver Island.

It was with careful analysis that Ahousaht decided how to balance environmental and economic outcomes, said Tyson Atleo, a hereditary leader of the nation whose territory spans Clayoquot Sound, a globally recognized biosphere reserve.

Ahousaht has largely done the work without major public funding, he said. Instead, the nation has secured grants and support from organizations including Nature United, the charity where Atleo works as natural climate solutions program director.

“This is long and hard work that is a part of nation building,” Atleo said.

“You need to have a vision, and in order to have a vision, you need to have the resources, and in order to implement the vision you need to have partnerships with Crown governments, likely corporations, as well as supporting (non-governmental) partners, and you need to have a vision for your economic future,” he said.

The neighbouring Hesquiaht and Tla-o-qui-aht nations were working on similar plans in the fall of 2020, when the BC government issued an order to defer logging across more than 170,000 hectares of old-growth forests around Clayoquot Sound, while it works with the nations to establish permanently protected areas.

Ahousaht was in favour of deferral because the nation believes “very strongly (in) preservation of old-growth systems … not just for the potential economic benefits of protection, but for the ecological and cultural benefits,” Atleo added.

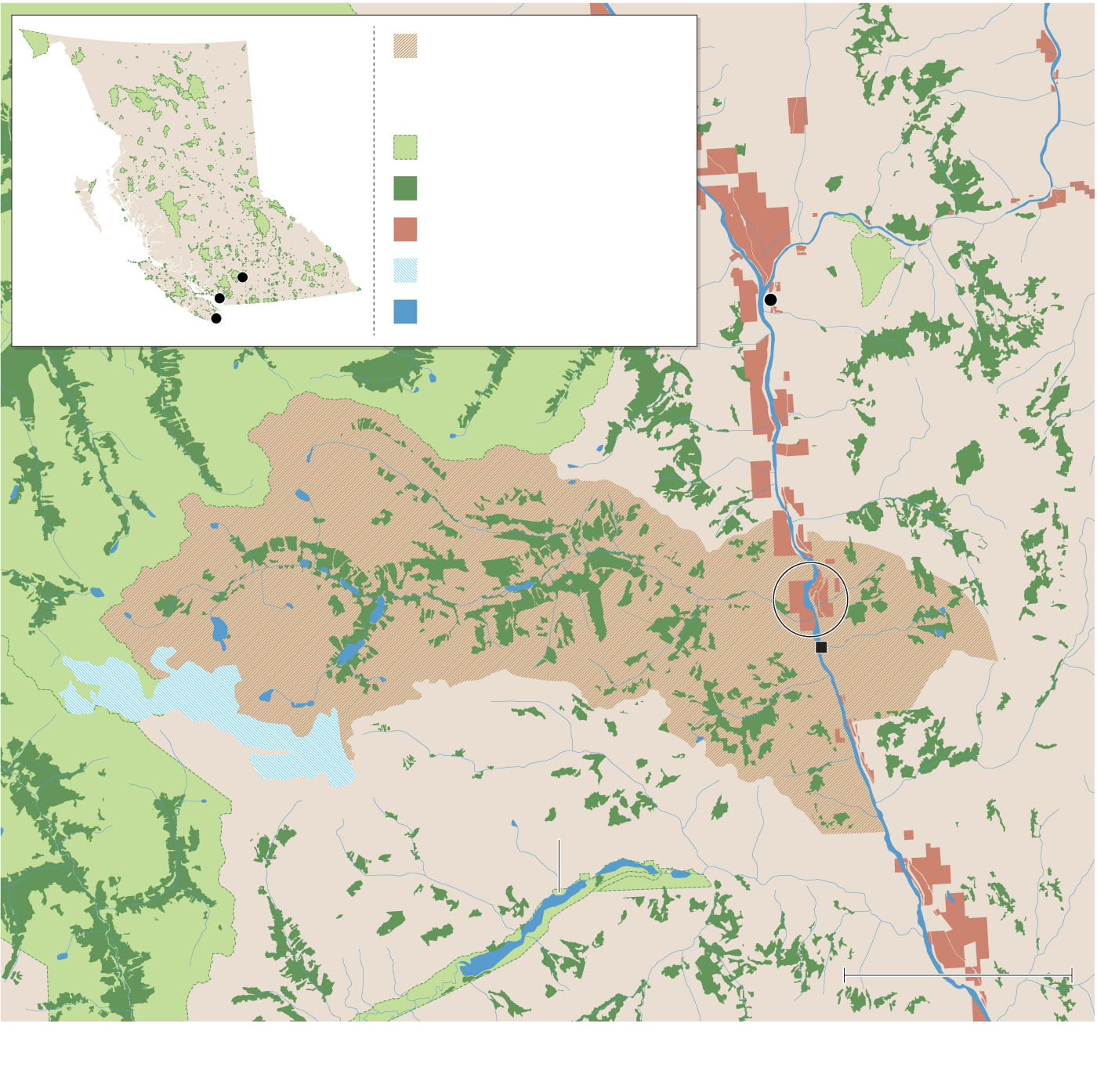

A year ago, BC announced that an expert panel had mapped 2.6 million hectares of old-growth forests identified as “rare, at-risk, and irreplaceable.”

At the same time, the province asked 204 First Nations to decide whether they supported the deferral of logging in those areas for an initial two-year period, allowing time for the province to develop “a new approach to sustainable forest management that prioritizes ecosystem health and community resiliency.”

However, it has yet to announce significant funding to support the complex process for nations to consider how to preserve old growth while developing alternative sources of revenue and economic opportunities aligned with stewardship goals.

Conservation comes with economic costs, said Atleo, especially in communities that depend on forestry revenues. It must be paired with some kind of compensation or support for sustainable economic diversification, he said.

“The philanthropic community is stepping up and offering a stewardship endowment in the case of (Clayoquot Sound) because of the high biological diversity in the region, but it’s a model that we should be looking at publicly,” he said.

“The government might not have a long-term vision, which for me means there’s space for nations to step up and define what that vision might be,” he added.

In its most recent public update on deferral areas provided nearly eight months ago, the Forests Ministry said the province had received responses from 75 First Nations in support of deferrals across 1.05 million hectares of at-risk forests, while 60 had requested more time and seven had indicated they didn’t support the plan.

In response to a request for the total area set aside in the first year of the deferral process, the ministry said it’s working toward an update in the near future.

Unless a First Nation expresses support for deferrals in its territory, the areas remain open to potential logging and applications for new logging permits.

About 9,300 hectares of the proposed deferrals — an area 23 times the size of Vancouver’s Stanley Park — have been logged over the last year, the ministry said.

The deferral areas contain some of the largest and most ecologically important old-growth forests left in BC, said TJ Watt, a photographer whose images of ancient trees before and after logging first captured global attention in 2020.

Watt’s photos from the Caycuse watershed on southwestern Vancouver Island show massive trees, then their stumps after they were cut. Some were logged a few months before they were identified as part of the deferral process, he said.

About 15,000 hectares of the proposed deferral areas had already been logged in the year leading up to the announcement last November, the Forests Ministry said.

Another area in the Caycuse was logged a couple of months after the start of the deferral process, said Watt,who uses GPS, geo-tagging on his photos, publicly available data and satellite images to confirm the location and status of cut blocks.

The province’s publicly available mapping shows cut blocks overlapping with proposed old-growth deferral areas in the Caycuse and other areas across BC.

The Caycuse watershed is located in Ditidaht First Nation territory.

Reached by phone, Ditidaht Chief Councillor Brian Tate said he had a full schedule and couldn’t comment on old-growth logging in the nation’s territory.

Teal-Jones, the forestry company that holds the rights for cut blocks in the Caycuse watershed, said in a statement it is not harvesting in areas that have been deferred.

Watt said he feels BC is putting First Nations in an unfair position by asking them to choose between generating forestry revenue and pausing logging without compensation or support for sustainable economic and ecological development.

Conservation financing is the key element that enabled the large-scale protection of old-growth forests in the Great Bear Rainforest, said Watt, a National Geographic explorer whose work was funded by the Royal Canadian Geographic Society.

It could mean developing eco-tourism or sustainable fisheries, or expanding Indigenous Guardian programs, which support a variety of land-based jobs.

“None of this can happen for free,” Watt said.

“It takes some leadership from the province to say, ‘We’ve taken from you for more than a century, now we’re asking you to protect these forests because it’s an ecological emergency, here is how we’re going to help make thatpossible’,” said Watt, who works with the Ancient Forest Alliance, a BC-based advocacy group.

In an email, the Forests Ministry said BC is currently working to establish a new conservation financing mechanism to support permanent old-growth protection.

The BC government began sharing forestry revenues with First Nations in the early 2000s. Last spring, it more than doubled the amount it shares with eligible nations, leading to an estimated increase of $63 million this year, the ministry said.

In response to a series of questions, the ministry said the increase would “more than offset” any short-term revenue impacts arising from old-growth deferrals.

The province has not received any direct requests from First Nations for compensation as a condition for supporting the temporary deferrals, it said.

BC provided just shy of $12.7 million over three years to support First Nations through the deferral process, amounting to about $20,000 per year for each nation.

At the time, Grand Chief Steward Phillip with the BC Union of Indian Chiefs called that funding “totally insufficient to undertake the work.”

The province’s 2022 budget earmarked $185 million over three years to support the forest industry, its workers, and First Nations through the deferrals.

Watt noted the federal government committed up to $55.1 million over three years to establish a BC “Old Growth Nature Fund” in its budget earlier this year.

The money would be available in 2022-2023, but it’s conditional — the BC government must match the federal investment in order to establish the fund.

BC’s Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship did not answer a question about whether the province plans to match Ottawa’s pledge.

Dallas Smith, a member of Tlowitsis Nation on the east coast of Vancouver Island who helped negotiate the Great Bear Rainforest protection agreement, said the lack of funding is a gap in the deferral process, and BC has yet to communicate a clear plan to help First Nations with long-term planning.

“Even if nations wanted to protect more, (the province) didn’t have capacity to sit down and deal with all those nations and actually have a planning process,” said Smith.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 27, 2022.

Read the original article. [Original article no longer available]