Twenty years after clash at Clayoquot Sound, activists see new wave of unrest on the horizon

Twenty years after a protest led to massive arrests on logging roads in Clayoquot Sound the organizers say a lot has changed – but a lot hasn’t, and they predict a new generation of activists may soon be on the barricades again.

The issue next time could be pipeline development or, once again, logging.

Where or when remains unpredictable, as was the Clayoquot rally. That summer thousands of people flocked to camp out in the Black Hole, just outside Tofino on Vancouver Island, and to stand in ranks across logging roads despite threats of arrest by the RCMP.

Hundreds were dragged away. But the Australian band Midnight Oil rocked through the night and the next day people got up and defied the law again.

The event threw the NDP government into shock – and led to a negotiated compromise. Clear-cut logging, then a practice favoured by industry and government, would be ended and a scientific panel would guide logging in the area.

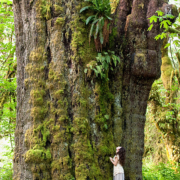

It was a dramatic victory – but it didn’t end the environmental problems in B.C. Clayoquot Sound is still being logged and a mine is proposed in the area. B.C.’s Interior forests are currently being logged at a rate many say is unsustainable. Old-growth trees, some more than 1,000 years old, are routinely cut down. The Port of Metro Vancouver is pushing for increased coal shipments – and two separate oil pipeline projects are being proposed in B.C., despite widespread public concern.

“People have asked me many times, is there going to be another Clayoquot? Is this the next Clayoquot? Is that the next Clayoquot?” said Valerie Langer, a key organizer of the 1993 protest who was then with Friends of Clayoquot Sound.

“But I don’t think you manufacture things like Clayoquot ’93,” she said. “That was a factor of a broad provincewide tension about forestry, a good place to focus that [concern] – and a group that was ready to fly with it.”

However, all those factors could easily come together again in B.C., said Ms. Langer, who is now with the environmental group, ForestEthics Solutions.

“I do feel that kind of happening with the tar sands/pipeline campaign,” she said, referring to the movement to stop Enbridge Inc. from building its proposed project across B.C.

Ms. Langer said the Clayoquot protest seemed to come out of nowhere, but the mood that drove it had actually been building for years, as the government allowed industry to clear cut the forests of B.C., despite growing public objections.

She senses that same “kind of desperate feeling” simmering in the public now over the prospect of a pipeline snaking across the province to feed a parade of oil tankers plying the waters of the Great Bear Rainforest.

“I don’t think the federal and provincial governments have really cottoned on to that [public unrest] yet,” said Ms. Langer. “But this is something that builds and then there is a moment – and you never know exactly where and exactly when that will be – when it explodes.”

Vicky Husband, who was head of the Sierra Club in B.C. in 1993, said one of the reasons the Clayoquot protest got so big so fast was because people could easily drive to the area to see for themselves what environmentalists were complaining about.

The highway from Port Alberni to Tofino cut right through an active logging area, including the Black Hole, where the old-growth forest had been stripped, and then the landscape burned.

“Clayoquot Sound and Tofino were at the end of the only paved road to the open Pacific. And that’s critical. People could get there. They could see the horror show of what was going on with the logging,” she said.

Ms. Husband said she’s alarmed at the level of logging now taking place in B.C., and at government plans to privatize public forest lands. She’s horrified by the prospect of oil pipelines crossing B.C.

Do you think, she was asked, that we need another big environmental protest in B.C?

“Yes, I do,” she said, “because I don’t think we have a government that understands.”