Mowachaht/Muchalaht awarded $15 million to protect old growth and salmon

November 10, 2023

By Eric Plummer

Ha-Shilth-Sa News

Original article here.

Nootka Sound, BC

A project to protect a significant portion of Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory has been pledged $15 million from the federal government, fueling an initiative to save old growth and salmon populations in Nootka Sound over the next generation.

On Oct. 30 Canada’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change sent a letter to Eric Angel, project manager for the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation’s Salmon Parks initiative. This confirmed over $15 million in funding for the project, payable up to March 31, 2026.

“I seek the highest level of environmental quality in order to enhance the well-being of Canadians,” wrote Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault. “In this regard, one of my priorities is to advance conservation of biodiversity and sustainable development.”

Other funding has been secured from the Ancient Forest Alliance, the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, the Indigenous Watershed Initiative, Nature Based Solutions Foundation, Nature United and the Sitka Foundation, as well as other organizations providing expertise at no cost.

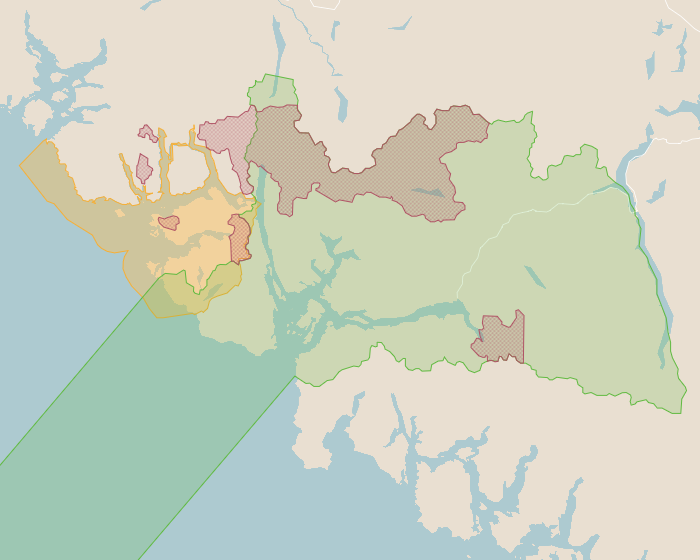

The project, which is titled ‘Mowachaht/Muchalaht Salmon Parks Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area – Old Growth Estuary Protection’, is designed to conserve critical parts of the territory by changing the tide of industrial activity in Nootka Sound.

“Salmon parks, fundamentally, is about setting things right again in this wonderful part of the world so that the chiefs are in a position to look after the ha-hahoulthee,” explained Angel during a tour of the Salmon Parks in October.

A major part of setting things right is halting logging in the designated areas. According to the Salmon Parks project application, at the current rate of harvest all old growth forests in Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory will be logged in the next 15 years.

As industrial forestry developed in the region, wild salmon populations in Nootka Sound have declined by 90 per cent, according to the project description, and could become extinct in the next 20 years without serious intervention.

“Old growth ecosystems are salmon ecosystems. They evolved together,” said Angel.

“We’re witnessing another extirpation series, small extinctions of salmon throughout the Pacific northwest,” he added. “There’s no one cause of that, but old growth forests, the destruction of them has been nothing short of catastrophic for salmon populations.”

The federal funding allows the Salmon Parks project to protect 38,868 hectares of old-growth forest, areas in Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory that contain “critical salmon ecosystems”, according to the application. The majority, or almost $12.5 million, of the federal funding is set aside for land acquisition costs, such as the buyouts of tenures held by forestry companies on the Crown land. Currently Western Forest Products and BC Timber Sales hold these tenures, which are legally recognized under provincial law.

A clearcut on Nootka Island. Photo by TJ Watt.

“We have to deal with the existing industrial and commercial interests on the landscape,” explained Angel. “That’s primarily forestry, and they’re going to want to be compensated.”

The Salmon Parks are already recognized under Mowachaht/Muchalaht law, but provincial designation is now necessary for the areas to be protected into the future.

“For Salmon Parks to be considered by the chief forester, or any other agency for that matter, requires some form of legislated protection,” said Roger Dunlop, the project’s technical lead and Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s Lands and Natural Resource manager.

“British Columbia made a huge mistake when they decided to liquidate all the timber harvesting land base, which means every tree in British Columbia that’s accessible,” continued Dunlop. “This is the nation’s alternative to that mistake.”

The federal funding will also go towards professional services necessary for Salmon Parks as well as external contractors and guardians from the Mowachaht/Muchalaht community to monitor and report on the designated areas.

It’s possible that Jamie James could play a leading role in this management. The First Nation’s field logistics coordinator spent his childhood on the shore of Muchalaht Inlet in Ahaminaquus, where his father taught him how to fish.

“It was really about living off the land, understanding what it meant to provide for the family but also for the community,” said James, who is concerned about carrying on the teachings of sustainability from his father, who grew up in Yuquot. “Once you start losing all of this stuff, you can no longer depend on the land to make a livelihood. That’s what scares me a lot.”

Although industrial-scale logging will no longer be permitted in the Salmon Parks, other small-scale activities can continue, particularly hunting, fishing and the cultural harvesting of trees.For James, these traditional practices are part of an interconnected way of living that he hopes the Salmon Parks will foster, a network that includes animals and people who rely on salmon-bearing streams.

“The broader part of the whole thing about the Salmon Parks, to me, is really being able to protect the landscape, the habitat, the resources, the environment – the sustainability for people that depend on all those things,” he said. “It’s the connection of all those things that depend on those resources.”

“As humans, we need to adapt to nature itself, rather than getting nature to adapt to us,” said James.

The old growth forest that Ottawa recently funded for protection is part of 66,595 hectares of critical habitat in Mowachaht/Muchalaht territory that the Salmon Parks project encompasses. The First Nation hopes to have this whole area protected by 2030 – the same year that the federal Liberals and have pledged to have 30 per cent of Canadian waters and land protected.

On Nov. 3 the feds put serious money behind this promise, with the announcement of the Tripartite Framework Agreement on Nature Conservation. The result of negotiations between the federal government, the province and the First Nations Leadership Council, this brings a fund that could reach over $1 billion over the course of the agreement, shouldered equally by Ottawa and the B.C. government.

Although the Government of Canada cannot declare IPCAs in a province, the agreement could lead to such designation in a First Nation’s territory.

“The Framework agreement supports a collaborative approach to landscape-based ecosystem health and biodiversity conservation in B.C.,” wrote Cecelia Parsons, a spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada, in an email to Ha-Shilth-Sa. “The agreement will support indigenous partners establish Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas.”

Mowachaht/Muchalaht member Jamie James grew up on the short of the Muchalaht Inlet in Ahaminaquus, where his father taught him how to fish. (Eric Plummer)

This story was made possible in part by an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.