February 27, 2023

The Narwhal

By Sarah Cox

Almost two decades after the Williamson’s sapsucker was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, the BC government continues to sanction logging in the bird’s old-growth forest critical habitat.

Biologist Les Gyug was working for BC’s environment ministry when a logging permit application caught his eye. A forestry company planned to clearcut rare old-growth larch stands in the province’s southern interior, set aside decades earlier as seed trees to allow for natural regeneration. “Rather than log them, let’s go look, and see what’s in them,” Gyug recalls saying.

He expected to find a suite of forest birds in the scattered 400-year-old western larch stands: birds like Townsend’s warblers, gaily-coloured western tanagers and brown creepers, a small songbird that spirals up tree trunks. Walking through the trees after dawn, binoculars in hand, he heard a mysterious bird drumming in staccato rhythm. “I had never heard this before. And I realized only afterwards, ‘Jeez, that was a Williamson’s sapsucker and it was in an old larch stand!’ ”

Back then, in the mid-1990s, little was known about Williamson’s sapsucker — the only one of the world’s 250 woodpecker species where the plumage of males and females is so strikingly different they were once thought to be two distinct species.

Gyug became a global expert on the bird, whose males have a lemon yellow belly and a distinctive cherry-red patch on their chin and upper throat. Females are banded in black and white, with a tawny head and a yellowish patch on their belly.

“I’ve found my niche,” Gyug says. “I could have just as happily worked on pelicans or something else. But this was a mystery bird. We didn’t have a clue how many there were. We only had a general sense of what their habitat needs were.”

Surveys conducted by Gyug and other biologists found only about 450 Williamson’s sapsucker pairs in BC, the only place in Canada where they live. Populations were dwindling. And the sapsucker’s old-growth habitat was vanishing, primarily due to logging. It all added up to an endangered listing under the federal Species at Risk Act in 2006.

But that wasn’t enough to protect the sweet-toothed bird, which migrates to BC every spring from Mexico and the southwest U.S. Nor did a BC Conservation Data Centre summary report, rating logging threats to the sapsucker as “high,” make any difference. The government-run data centre, which collects scientific data about species and ecosystems, singled out western larch logging in the woodpecker’s Okanagan-Boundary and Kootenay ranges as a particular concern.

The BC forests ministry continued to sanction logging in the sapsucker’s federally designated critical habitat — the habitat necessary for a species to breed and for populations to recover — including in western larch forests in the Okanagan-Boundary and Kootenay regions.

“Critical habitat is still being logged,” Gyug tells The Narwhal. “If we keep losing it, [the sapsucker] will never get off the endangered list … And right now, we’re just not doing enough.”

Sapsucker ‘condos’ are falling to the ground

Williamson’s sapsuckers often nest in a single old-growth western larch — a sapsucker “condo” — where they excavate holes the size of a toonie and raise three to five chicks.

Like maple syrup farmers, they tend sap trees, visiting a handful of Douglas firs, larches and pines several times daily during breeding season to tap new wells or keep existing wells flowing. Woodpeckers have barbs on their tongues to latch onto insects and grubs; the Williamson’s sapsucker has a brush-like tuft on the edge of long tongues for licking up sap.

Williamson’s sapsuckers also feed on carpenter and western thatching ants that hustle up and down tree trunks to tend aphid colonies on branch tips. The ants have a symbiotic relationship with the aphids. They protect them from predators, carry them to their nests at night and during winter and milk their antenna for sugar-rich liquid secretions called honeydew.

“You’ve got to have trees because they take ants off tree trunks; if tree trunks aren’t there, they can’t make a living,” Gyug explains. “They need the nesting trees and they need foraging habitat — you need the combination of the two in close proximity to each other.”

Gyug’s work saved the western larch seed stands from logging. Over time, he also helped secure the designation of about 150 small, scattered wildlife habitat areas for the sapsucker. But the wildlife habitat areas only represent about three per cent of the territory the sapsucker occupies in the province, leaving the majority open to logging and other disturbances.

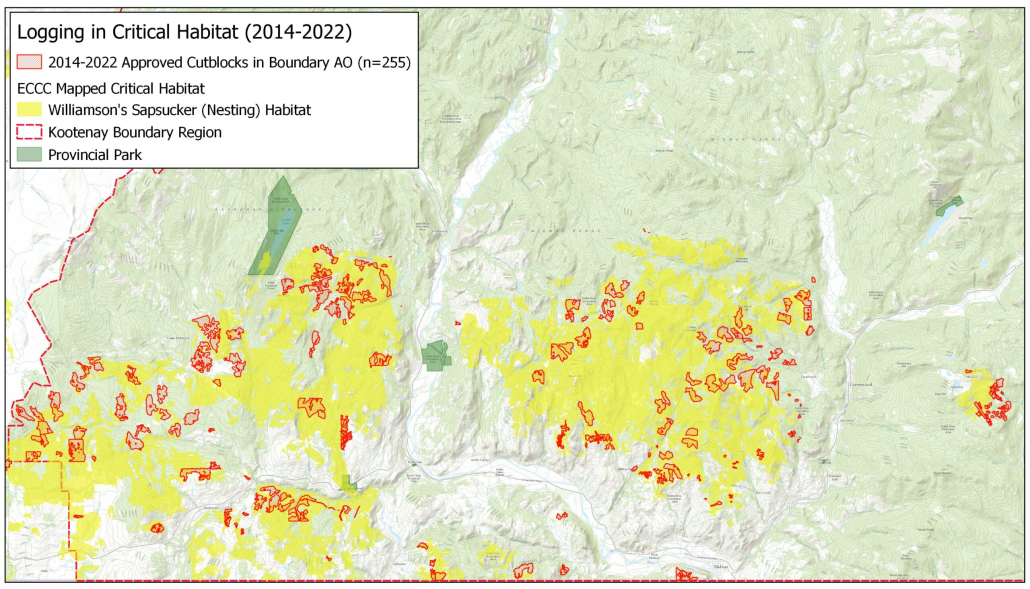

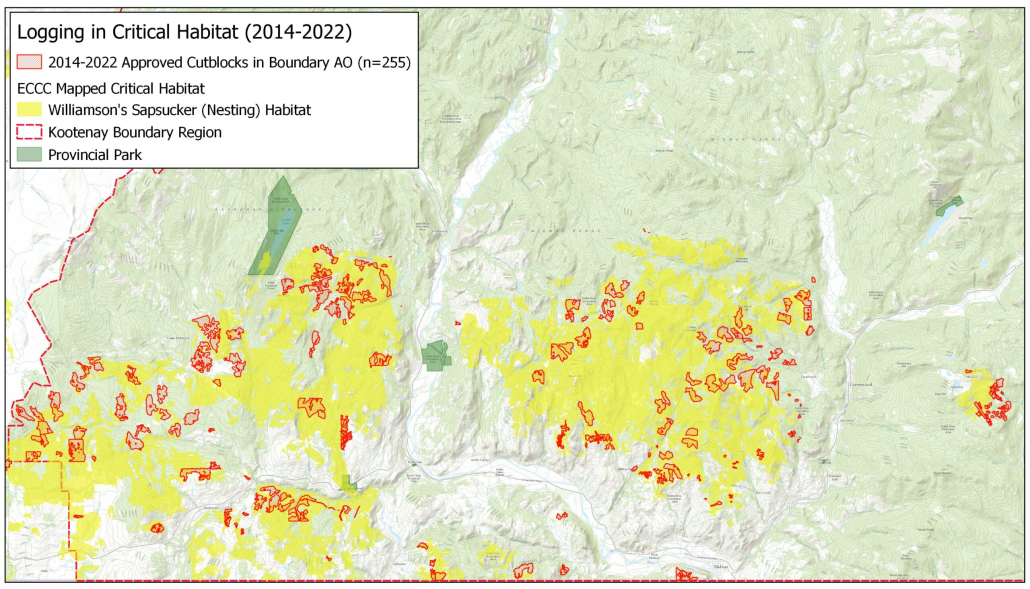

In the Boundary region, about 15 per cent of the sapsucker’s federally designated critical habitat was clear-cut from 2017 to 2022, according to wildlife biologist Jared Hobbs. Sapsucker “condos” fell to the ground. Hobbs says logging is likely taking place at the same rate, or even more extensively, in the other two areas where sapsuckers live — the east Kootenays and the Merritt-Princeton area. “In the other regions they’re logging like crazy as well.”

Hobbs recently helped document 182 cutblocks, covering more than 3,000 hectares, in federally mapped Williamson’s sapsucker critical habitat within the Boundary area (a small portion of the Okanagan-Boundary region). He found a nest tree logged — “not an uncommon occurrence” — even though the slow rot and hard shell that makes the trees desirable for the sapsucker and other cavity dwellers means they are of little or no commercial value to the forest industry.

The BC government continues to sanction logging in federally designated critical habitat for the Williamson’s sapsucker, including in BC’s Boundary region.

“These trees are so valuable that with every one that’s lost, you are eroding the recovery potential of the population,” Hobbs says. “It takes hundreds of years to replace that tree cut down by the timber industry. It’s cut down as garbage and left lying on the ground. And that was gold for the Williamson’s sapsucker.”

If logging in the sapsucker’s critical habitat continues, Hobbs says populations will reach a critical tipping point. He points to the northern spotted owl as a cautionary tale. Only one wild-born spotted owl remains in Canada, despite years of warnings from biologists about impending population collapse following widespread industrial logging in the owl’s old-growth rainforest habitat in southwest BC.

When a species falls below what biologists call its minimum viable population, decline quickly becomes irreversible — as in the case of spotted owls, cod on the east coast and southern mountain caribou populations in BC Individuals struggle to find mates and reproduce, while genetic diversity — necessary for good health and adaptations, including to environmental shifts wrought by climate change — is lost.

“At that point, the crash is catastrophic and irreversible,” Hobbs says. “That’s what we did to the spotted owl. And we’re about to do that with the Williamson’s sapsucker. At that point, no matter what you do, and how much in recovery dollars you throw at it, like caribou and spotted owls, you’re not going to pull it back. The challenges become insurmountable.”

Williamson’s sapsucker populations in BC are genetically valuable because they’re at the northern extent of their range and have adapted to a different environment than U.S. populations, making them essential to help the species adjust to climate change and other stressors, Hobbs says.

“These are not populations that should be dismissed, they should be cherished.”

‘Nothing happens’ to save sapsucker

For Sean Nixon, a lawyer with the environmental law charity Ecojustice, the plight of the Williamson’s sapsucker is all too familiar. Many old-growth forest-dependent species in BC are in trouble, Nixon notes. “We know the causes of the decline. Generally commercial logging is the primary threat. We know what needs to be done to save the species. But then nothing happens.”

In large part, that’s because BC has no legislation dedicated to protecting and recovering the sapsucker and 1,340 other species at risk of extinction in the province. The BC NDP campaigned on a promise to enact endangered species legislation, but quietly reneged after coming to power in 2017.

The federal Species at Risk Act automatically protects critical habitat for most at-risk species only on federal land, a scant one per cent of BC.

The Act nominally protects migratory bird nests on provincial land. But enforcement is almost impossible, Nixon observes. Nests would have to be identified in advance of logging and other destructive activities and “there aren’t federal enforcement officers in most places.”

“Generally, industry and the provincial government do very little to survey an area in advance of logging to see if it contains nests and where they are.”

Forests occupied by the Williamson’s sapsucker could be safeguarded if the federal cabinet issued an order under the Act to protect the critical habitat of migratory birds, which fall under federal jurisdiction.

But Nixon doubts an order will be forthcoming. Reluctant to tread on the jurisdictional toes of the provinces, the federal government has issued emergency orders only for two species in the 20-year history of the Act — the western chorus frog in Quebec and the greater sage-grouse in Alberta. Federal cabinet will also soon consider issuing an emergency order to protect the northern spotted owl.

The provincial government will sometimes voluntarily designate wildlife habitat areas for the Williamson’s sapsucker and other at-risk species, Nixon notes. Yet road-building and some logging are still permitted in wildlife areas.

“They’re not required to follow objective scientific advice, like the advice in the federal recovery strategy, about how big those areas need to be, where they need to be, what kinds of activities they need to prohibit,” he says. “They’re just kind of ad hoc postage stamps on the landscape.”

When asked why the province allows federally designated critical habitat for the Williamson’s sapsucker to be destroyed, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship did not respond directly. Instead, the ministry said the government has established many wildlife habitat areas for the sapsucker and best management practices are in place for timber harvesting, roads and silviculture.

The ministry also sidestepped a question asking why the province has turned a blind eye to to nest tree logging, saying trees occupied by the sapsucker are protected under the BC Wildlife Act, while the federal Migratory Birds Convention Act prevents nests from being disturbed or destroyed.

Asked what steps the government is taking to prevent further destruction of the sapsucker’s critical habitat, the ministry said the province is continuing work, in partnership with First Nations, to develop a declaration prioritizing ecosystem health and biodiversity conservation.

Biologist calls lack of action ‘disheartening’

Ecojustice says Ottawa has embraced a “dangerously narrow” interpretation of its duty to protect the critical habitat of at-risk migratory birds under the Species at Risk Act. Under that interpretation, the Act protects only nests, not any other habitat necessary for the survival and recovery of at-risk migratory birds. In the case of a secretive bird such as the at-risk marbled murrelet, which lays a single egg on a mossy branch high in an old-growth tree, nests are almost impossible to find.

“The key problem is that nests are very hard to identify from the ground for most species,” Nixon says. “The birds do a very good job of hiding them. And they’re generally quiet or they disappear as soon as people show up.”

Last year, on behalf of Sierra Club BC and the Wilderness Committee, Ecojustice announced it is suing the federal government for failing to live up to its statutory duties to protect habitat necessary for survival and recovery of migratory bird species.

If Ecojustice wins the case, scheduled to be heard in federal court this spring, Nixon says the federal government will be obliged to take steps to ensure protection of the sapsucker and other at-risk migratory birds.

A win would compel federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault to regularly recommend cabinet issue an order to protect migratory bird habitat on provincial land, including the old-growth stands where the Williamson’s sapsucker nests and feeds, according to Nixon.

“It would basically be the government stepping in and doing what the province hasn’t been willing or able to do: namely, set aside and protect and conserve the habitat that these species need to survive and recover.”

Hobbs says Williamson’s sapsuckers have an intrinsic right to live in the forest. That right is acknowledged in the preamble to the Species at Risk Act, which states, “Wildlife, in all its forms, has value in itself.”

“It’s really hard to find these old-growth patches that can sustain Williamsons’ sapsucker,” Hobbs says. You can spend days hiking around and not get into a patch that’s good enough. And then you do get to one and find that it’s just been logged. And then you find it’s in critical habitat, which the province is supposed to recognize and afford effective legal protection to.”

“Yet the BC forest ministry is approving the [cut]blocks in these habitats. It’s really disheartening.”

View the original article.