CNN: Striking photos show how our planet is changing – for better and for worse

A photograph of a solitary man walking along terraces in China, rust-red rivers in Alaska and a gargantuan western red cedar are among the winning images of the Earth Photo 2024 competition. The award – created in 2018 by Forestry England, the UK’s Royal Geographic Society and visual arts consultancy Parker Harris – aims to showcase the beauty of our planet, as well as the threats it is facing, from climate change to toxic pollution.

Times Colonist: Photo of old-growth cedar tree on Flores Island wins international award

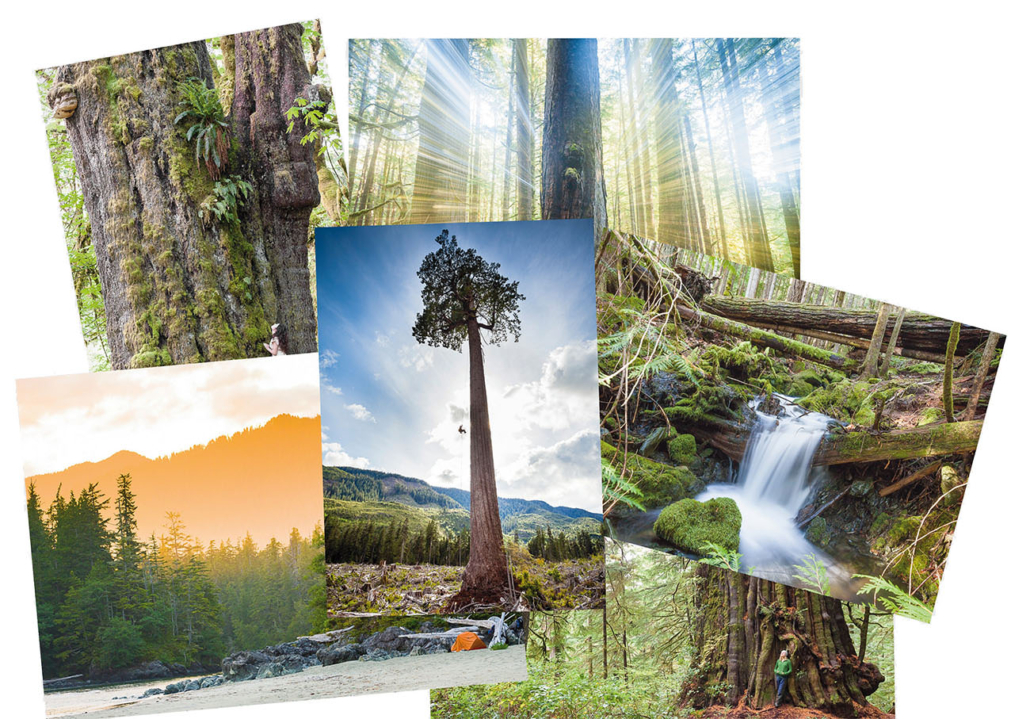

An image of a massive western red cedar towering over an Ahousaht hereditary leader has won an award in the Royal Geographical Society’s Earth Photo 2024 competition. Titled Flores Island Cedar, the photo shows Tyson Atleo standing at the base of a western red cedar that’s estimated to be more than 1,000 years old.

Your Donations will be DOUBLED until July 21st!

We're excited to announce that donations to the Ancient Forest Alliance will be matched dollar-for-dollar up to $20,000 until July 21st! For the next month, when you give a gift to the AFA, it will have DOUBLE the impact!

Photo of Giant Old-Growth Cedar Wins Prestigious International Award

Ancient Forest Alliance Photographer TJ Watt awarded Royal Geographical Society Earth Photo 2024 prize for Image of the Enormous Tree in Clayoquot Sound, Canada, featured on CNN and in The Guardian. The award coincides with the largest old-growth protected areas victory in decades announced earlier this week in Clayoquot Sound.

Clayoquot – Biggest Old-Growth Protected Areas Victory in Decades

Conservationists are applauding the leadership of the Ahousaht, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and BC NDP government for yesterday declaring the protection of 76,000 hectares of land in new conservancies in Clayoquot Sound near Tofino.

Financial Review: Why we should embrace tall-tree tourism

This article explores tall tree tourism in Port Renfrew, the "Tall Tree Capital of Canada," along with the economic and environmental benefits of preserving ancient forests like Avatar Grove on Vancouver Island.

AFA Greeting Cards are on sale for 20% off until August 31st!

AFA greeting cards, with photos taken by TJ Watt, are all on sale for 20% off all summer!

Times Colonist: Canada’s logging industry is seeking a wildfire ‘hero’ narrative

The Times Colonist debunks BC's and Canadian forestry associations' aim to tell a story that places them as the 'hero' in a fight against BC wildfires.

The Narwhal: Did BC keep its old-growth forest promises?

As the BC election looms, the Narwhal analyzes what progress has been made on implementing the old-growth forest recommendations and what more needs to be done.

BC Old-Growth Policy Update Adds Little To Current Commitments

The BC government has released an old-growth policy update outlining their plans to address the recommendations in the Old Growth Strategic Review. Here's our take.