Conservationists Commemorate 25-Year Anniversary of Clayoquot Sound Mass Protests, Call on BC Government to Finally Do the Right Thing and Protect Old-Growth Forests

Tofino, British Columbia – July 5th, 2018, marks 25 years since the launch of the Clayoquot Sound mass blockades against the logging of ancient forest in Clayoquot Sound by Tofino on Vancouver Island in Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations territory. Today, conservationists reflect on the impact of the historic movement and are urging the BC government to finally end the main forestry conflicts in BC by implementing science-based legislation to protect BC’s endangered old-growth forests, new regulations and incentives to foster a value-added, second-growth forest industry, and support for First Nations land use planning and sustainable economic diversification.

See a new video trailer regarding Clayoquot Sound and BC’s old-growth forests at: https://youtu.be/BreQMR_JrEo

In the summer of 1993 thousands of Canadians came to Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island, in the territories of the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples, to take part in the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history. The historic protests, organized by the Friends of Clayoquot Sound in Tofino, sought to put an end to the logging of endangered old-growth forests by timber giant MacMillan Bloedel. Over 12,000 people took part in the blockade of logging trucks over the summer, with almost 900 people being arrested. The protests garnered international media attention.

Eight years earlier, in an unprecedented show of solidarity, the Tlaoquiaht and Ahousaht First Nations were joined by local environmentalists to blockade logging of the biggest trees in Canada on Meares Island. These we first major protests against old-growth forest logging in Canada. The First Nations, in 1984, established Canada’s first Tribal Park there. Since then, the Tlaoquiaht have declared much of their territory as a Tribal Park, while the Ahousaht have developed a Land Use Vision, declaring over 82% of their territory, including all of the major intact areas, off-limits to logging.

“The movement for Clayoqout Sound – which includes the largest tracts of old-growth temperate rainforest left in southern British Columbia – was revolutionary in its impacts,” stated Valerie Langer, one of the lead organizers of the Clayoquot Sound campaign in the 1980’s and ‘90’s. “It galvanized a powerful environmental movement, strengthened First Nations rights and innovated the market campaign strategy, resulting in dramatic improvements in conservation and management in Clayoquot Sound. Elevating public understanding of old forests and clearcutting led to new environmental and land use policies in the province with a number of protected areas created in the ensuing few years. But the evidence is clear that we have yet to strike the balance between forestry and conservation on Vancouver Island and even some protection in Clayoquot is still outstanding.”

The movement also laid the foundation for science-based land-use planning and ecosystem-based management in the Great Bear Rainforest, and the expansion of First Nations resource management rights and land use planning across BC – all measures the NDP government has committed to employ to sustainably manage old-growth forests in BC going forward. It also gave rise to a generation of environmental activists.

“As a university student heavily involved in organizing the large urban rallies in Vancouver and the student blockade day in 1993, the momentous scale and impacts of the Clayoquot Sound movement imbued in me a lasting inspiration that has never left. My experiences from the Clayoquot movement of the early ‘90’s continues to energize me and sustain a resilience in me to keep fighting for nature and for a better world, decades later,” stated Ancient Forest Alliance executive director Ken Wu.

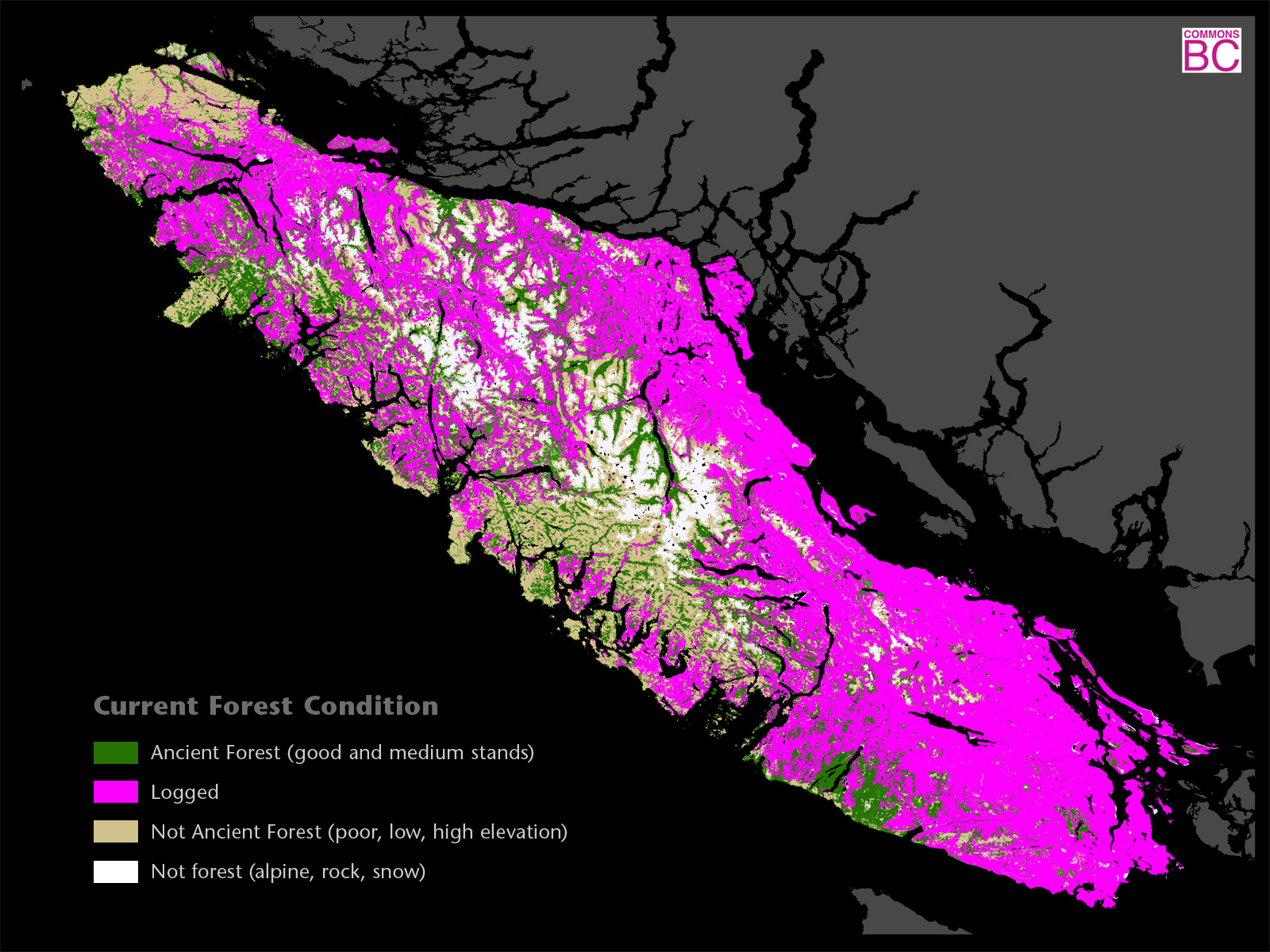

25 years on, much has changed in BC since the “War in the Woods” of the 1990s. Hundreds of thousands of hectares of prime old-growth forests have been logged; the BC economy has diversified; second-growth forests now constitute most of the productive forest lands in southern BC; the legal recognition of aboriginal rights has greatly expanded; and most people “get” it that old-growth forests can and should be protected due to the second-growth alternative for forestry.

Employment levels in BC’s forestry sector have also declined dramatically, from 99,000 jobs in 2000 to 65,000 in 2015, a loss of one-third of all forestry jobs. According to a 2008 study, the value of protecting old-growth forests now outweighs the economic benefits of logging them in large parts of the province.

In recent years, support for increased old-growth protection has expanded far beyond the environmental movement to include forestry workers and unions, businesses and Chambers of Commerce, and municipalities across BC. For example, the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM), representing mayors, city and town councils, and regional districts throughout BC, has passed a resolution calling for an end to old-growth logging on Vancouver Island; the BC Chamber of Commerce, representing 36,000 BC businesses, has called for expanded old-growth forest protection in BC in order to benefit the economy; and the Private and Public Workers of Canada (PPWC), representing thousands of BC forestry workers, are calling for an end to old-growth logging on Vancouver Island.

“The stage is totally set for a forward-looking, progressive BC government to protect our old-growth forests, ensure sustainable, value-added, second-growth forestry jobs, and to support First Nations land use planning and sustainable economic development. Doing so will finally put an end to the vast majority of the forestry and related land use conflicts in BC,” stated Wu. “Unfortunately, the large-scale industrial logging of endangered old-growth forests is still a reality in large parts of British Columbia, and the unsustainable high-grade depletion of our finest lowland ancient forests has resulted in the increasing collapse of species and ecosystems, the impoverishment of rural forestry-dependent communities and impacts on First Nations culture.”

Last year, several environmental groups, including the Ancient Forest Alliance, Sierra Club BC, and Wilderness Committee, presented a suite of policy recommendations to Forests Minister Doug Donaldson which would protect endangered ancient forests while ensuring sustainable, second-growth forestry jobs in BC. They included science-based old-growth protection legislation, financing for First Nations conservation-based economic development and land use planning, and incentives and regulations for a sustainable value-added forest industry.

“In their election platform, the BC government promised to manage BC’s old-growth forests based on the Ecosystem-Based Management approach used in the Great Bear Rainforest agreement, which resulted in the protection of most of the forests on BC’s Central and North Coast,” stated Andrea Inness, Ancient Forest Alliance campaigner. “So far, there have been no significant changes to the unsustainable status quo in forest policies in BC. We’re at a historic juncture, wherein we still have the ability to protect some significant tracts of the finest ancient forests on Earth. But time is running out for this government to take meaningful action,” stated Inness.

More Background Information

Clayoquot Sound is 260,000 hectares in size (2600 square kilometres or 1000 square miles). It lies on western Vancouver Island and consists of a major cluster of largely-intact ancient forest valleys and islands on the Pacific Coast. It is home to bears, wolves, cougars, deer, elk, marbled murrelet seabirds, and a vast array of biodiversity. Most of Clayoquot Sound’s forests – about 75% – remain old-growth, while the inverse is true across Vancouver Island, where 75% of the productive old-growth forests have been logged. The BC NDP government’s 1993 Clayoquot Land Use Plan protected only 33% of Clayoquot Sound’s land area, much of it bogs and marginal low-productivity forests with small trees, while releasing the vast majority of the area’s productive old-growth forests with large trees for the logging industry. The Ahousaht and Tlaoquiaht First Nation bands since then have designated most of their territories off limits to logging through their own land use planning processes, but the BC government has yet to officially endorse or financially support the Ahousaht Land Use Vision or the Tlaoquiaht Tribal Parks.

Old-growth forests are vital to sustaining unique endangered species, climate stability, tourism, clean water, wild salmon, and the cultures of many First Nations. Old-growth forests – with trees that can be 2000 years old – are a non-renewable resource under BC’s system of forestry, where second-growth forests are re-logged every 50 to 100 years, never to become old-growth again.

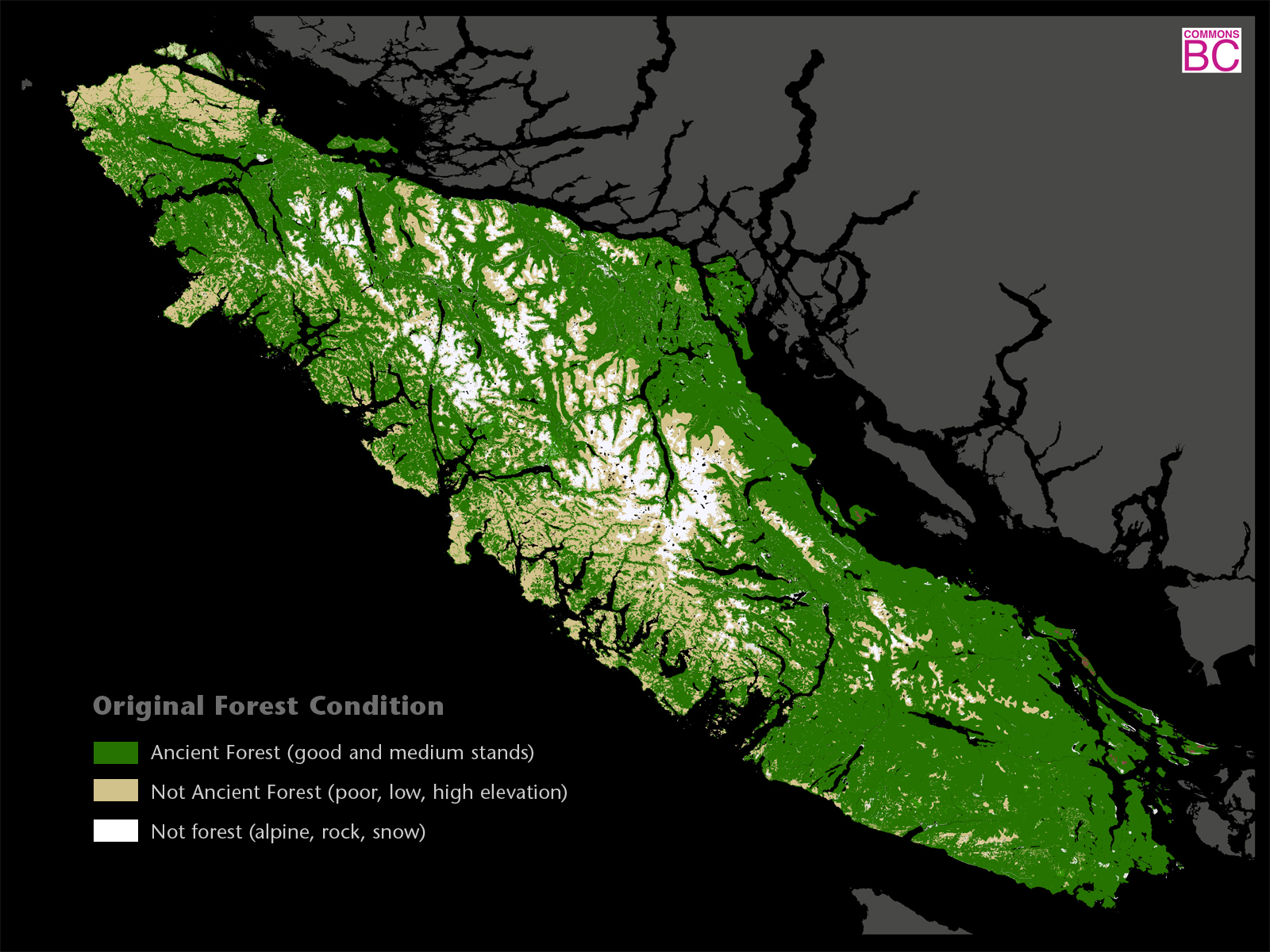

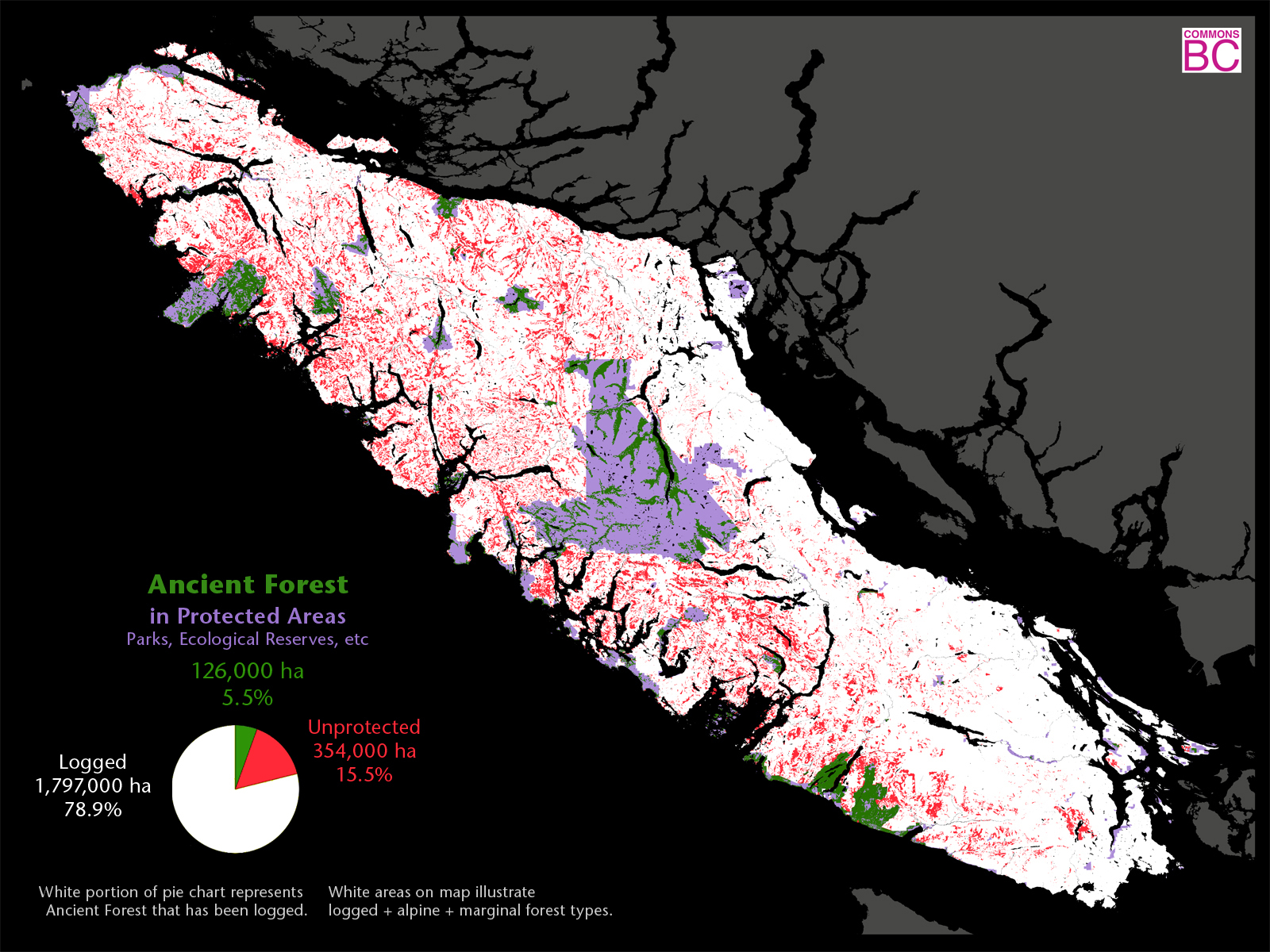

On BC’s southern coast (Vancouver Island and the southwest mainland), 75% of the original, productive old-growth forests have already been logged, including well over 90% of the valley bottoms where the largest trees grow. 3.3 million hectares of productive old-growth forests once stood on the southern coast (with an additional 2.2 million hectares of bog, subalpine forests, and other low productivity old-growth forests of low to no commercial value with stunted trees), and today only 860,000 hectares remain, while only 260,000 hectares are protected in parks and Old-Growth Management Areas. Second-growth forests now dominate 75% of the southern coast’s productive forest lands, including 90% of southern Vancouver Island, and can be sustainably logged to support the forest industry. See “before and after” maps and stats of the southern coast’s old-growth forests at: www.staging.ancientforestalliance.org/old-growth-maps.php

In order to placate public fears about the loss of BC’s endangered old-growth forests, the government’s PR-spin typically over-inflates the amount of remaining old-growth forests by including hundreds of thousands of hectares of marginal, low productivity forests growing in bogs and at high elevations with small, stunted trees, together with the productive old-growth forests where the large trees grow (and where most logging takes place). They also leave out vast areas of largely overcut private managed forest lands – previously managed as if they were Crown lands for decades and still managed by the province under weaker Private Managed Forest Lands regulations – in order to reduce the basal area for calculating how much old-growth forest remains, thereby increasing the fraction of remaining old-growth forests. See a rebuttal to some of the BC government’s PR-spin and stats about old-growth forests towards the BOTTOM of the webpage: https://staging.ancientforestalliance.org/action-alert-speak-up-for-ancient-forests-to-the-union-of-bc-municipalities-ubcm/