Explore Magazine: Speak for the Trees

See this article in Explore Magazine which features an interview with AFA's TJ Watt and covers the history of the Avatar Grove campaign, the economic value of standing old-growth forests, and debunks…

AFA 10-year anniversary celebration postponed

Ancient forest friends: To ensure the health and safety of our staff and supporters, we've decided to postpone our 10-year anniversary celebration on April 3rd in light of COVID-19.

We will reschedule…

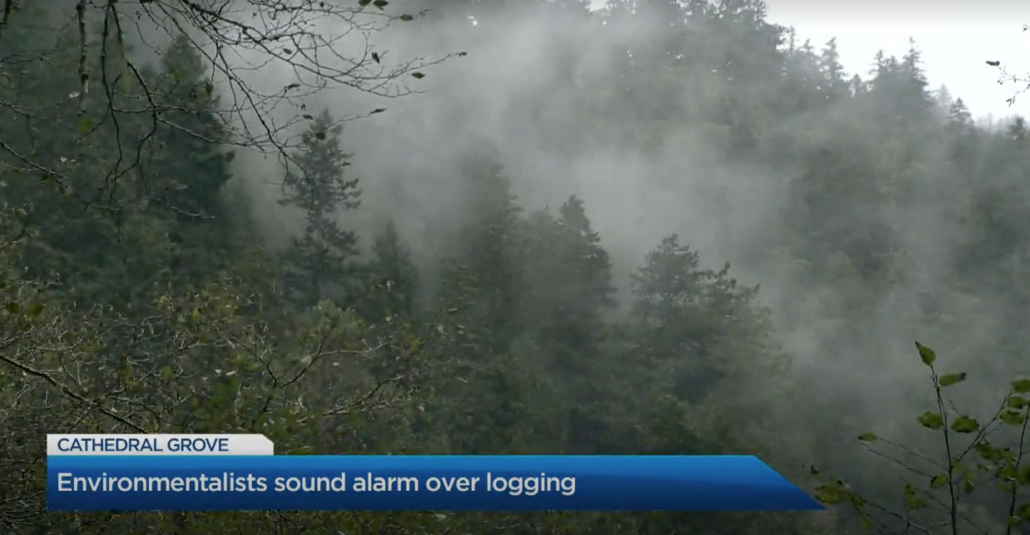

Cathedral Grove at risk from old growth logging uphill from popular site, say conservationists

Here's a CBC News article about clearcut logging of ancient forest "hotspot", Mt. Horne, located above Canada's most famous old-growth forest, Cathedral Grove.

Come Celebrate 10 years of the Ancient Forest Alliance!

Join the Ancient Forest Alliance on Friday, April 3rd, for a very special evening to celebrate our 10-year anniversary, our wonderful community of supporters, and the many accomplishments you've helped us achieve over the last decade.

Logging concerns around Vancouver Island’s famous old-growth forest

Watch this Global News piece about recent old-growth

clearcutting on the mountainside above Cathedral Grove, featuring AFA's Andrea Inness.

Old-Growth Logging on Mountainside Above Cathedral Grove Illustrates Urgent Need for BC Land Acquisition Fund for Protection of Endangered Private Lands

Old-growth logging on private lands on the mountainside above Cathedral Grove has put Canada’s most famous old-growth forest at risk and illustrated the urgent need for provincial funding to purchase and protect endangered ecosystems on private lands.

Today marks the 10-year anniversary of the AFA!

Today is the 10-year anniversary of the Ancient Forest Alliance and we're celebrating a decade of accomplishments made possible by YOU, our supporters!

Conservationists disappointed Budget 2020 fails to prioritize environmental protection despite climate and biodiversity emergencies

The Ancient Forest Alliance is disappointed the NDP government’s third provincial budget, released yesterday, once again fails to allocate even modest funding for the protection of endangered old-growth forests and other ecosystems.

Old Growth Forests Are Vital to Indigenous Cultures. We Need to Protect What’s Left

Tla-o-qui-aht canoe carver and artist Joe Martin shares valuable insights we can all learn from in his opinion piece in the Tyee.

For Vancouver Island’s old-growth explorers, naming trees is a delight – but saving them is a challenge

Check out this Globe and Mail article featuring the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance’s Ken Wu and the AFA’s TJ Watt, who recently located nearly two dozen(!) groves of spectacular but mostly unprotected old-growth Sitka spruce forest in the San Juan Valley in unceded Pacheedaht territory near Port Renfrew.